Artifacts of Accompaniment: Poetry Sites at Harvard University 2023-2024

~An excerpt from my thesis, days away from graduating divinity school~

This work would not be possible without those who have gone before me. Jacqueline Suskin, whose Poem Store and poetry typewriting work allowed me to dream up my own practice. Brian Sonia-Wallace, whose memoir The Poetry of Strangers describes how he wrote poems for people all across America. Audre Lorde, whose essay “Poetry is Not a Luxury” hangs on my bulletin board, and whose words I often say in prayer, “For there are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt…”

“Poetry keeps the door open to awe and ensures that we will find our way through the broken heart-field of wars, losses and betrayals…” —Joy Harjo

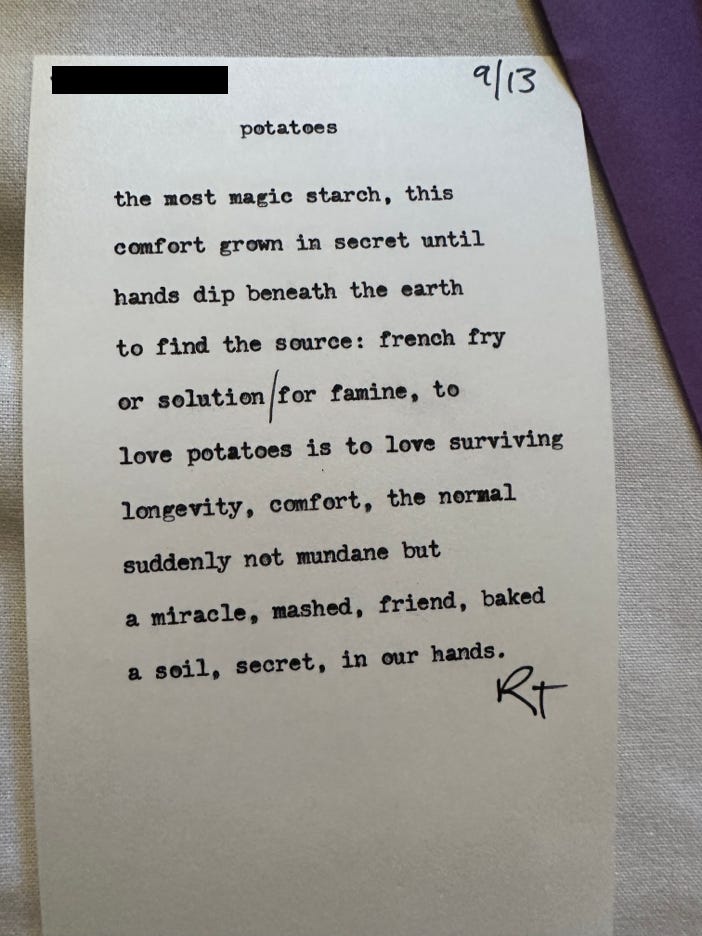

Nine times over the course of this year, I wrote poems for students and faculty in various locations across Harvard, for one to two hours, about whatever they needed most that day. Each site, I brought my Smith Corona Automatic 12 steel grey typewriter and a hot pink sign that said “POEMS.” When participants sat across from me, my opening question was usually, “What do you need a poem about today?” Over these two semesters, I wrote poems about sewing, hamsters, and unrequited love. I wrote poems about family, pet donkeys, a thesis about potatoes; poems about autumn, transformation, skin, birthdays, moss, slowness. I wrote poems for a chef who was falling for a doctor, and I wrote a poem for a resident at Mass Brigham who had made a mistake with a patient, who wept by my side in an empty room.

Poems about Gaza. Poems about Ukraine. Poems about friends who were Hamas hostages. Poems about connection, about reaching out a hand, about listening past where is comfortable.

The poems became record of courageous living.

This collection is over one hundred artifacts of connection, of moments where I set down my humming mind, my pain, and my fear— in order to listen. I listened for a spark, a sense of heat, an aliveness— where I could find a space of compassionate neutrality, where the threads of language could unfold a truth that sometimes I did not know was there until I started writing.

Over the course of these months, I noticed that more of my life— my conversations, my walks, my listening to birds, my phone calls— started to feel like one large site, even if I wasn’t always producing poems. This practice also changed my personal writing practice, and changed the poems that I edited and sometimes published. The two modes, which had always felt separate, began to feel more connected— like the chasm between the practices grew closer, permeable. It leaves me with the question: what is a “site” and what is simply the practice of close attention?

Philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm states in a 1974 seminar The Art of Listening, that listening “is an art like the understanding of poetry.” What is required is complete concentration and deep empathy. Fromm argues that “To understand another means to love him… Understanding and loving are inseparable. If they are separate, it is a cerebral process and the door to essential understanding remains closed.”

The poems were, and are, a gateway into an art of listening, an understanding that co-arises between two people.

When I read each participant their poem, they listened attentively to what I had created. In those moments, for the poem to be trustworthy, I required their presence as much as they required mine. One of the most surprising elements of this year was realizing how much I needed these sites— how much I needed and wanted to create a space to be listened to, not just for myself, but as a reminder of what’s possible.

When I described this project to people this year, one of the common questions that came up was, given that I was a candidate of a Master of Religion in Public Life, what this all had to do with religion. In the fall semester, I took Stephanie Paulsell’s course “Religion and Virginia Woolf.” During that course, we read Moments of Being, a collection of her autobiographical writings. In it, Woolf writes,

“From this I reach what I might call a philosophy; at any rate it is a constant idea of mine; that behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern; that we—I mean all human beings—are connected with this; that the whole world is a work of art; that we are parts of the work of art. Hamlet or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about this vast mass that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself. And I see this when I have a shock” (77).

Unlike Virginia Woolf, I might use the affirmative statement— that for me, these moments of connection, of careful listening, when time stops and it feels like the person and I are floating through the universe on a typewriter raft— that these moments are God. I am devoted to this way of showing up and loving, without any governance except the moment, as it is, in all its complexity.

I do not know how to be with this world’s magnitude of suffering, but I know how to meet one person at a time, with what they bring that moment. Perhaps these poetry sites are the only way I know how to be in contact with what is. It is my way of praying. It is where I find the sacred.

I’ve learned this year, in ways I didn’t know I needed to learn, how essential poetry is as a tool to attend to the difficult questions of our world. Somewhere, in the back of my heart or mind, I think I still carried the belief that poetry— that my great love, my deepest work— was frivolous, extraneous, absurd. How could I have carried that belief for over twenty years without realizing where it lived in me? It wasn’t a belief I chose, but one that had been handed down like the various terrible systems that organize the Western world.

This year, I saw how poetry opened up classes and difficult conversations; how it was poetry the doctors longed for in their moments of grief; how poetry could help create new language for the ground we now walk.

In Mayra Rivera’s essay “Embodied Counter Poetics,” which I read my first semester, she writes, “Are the humanities equipped to guide us toward this sense of embodied counterpoetics as both imaginative discourse and transformative practice—to counter the colonial and capitalist forces that shape our being? Do we need to invent new rituals, a counteraesthetic and a counterethics?” (114). Poetry is indispensable, as Mayra Rivera writes. It helps us understand “breaks in the experience of time.” It is a language of imagination, which is world-building. To imagine— and not just imagine, but to act on imagination— to choose to create instead of mimicking ways of communicating— takes courage.

These sites are improvisational, an investigation and “negotiation of the unknown,” to use a phrase from saxophonist and jazz composer Patricia Zarate Perez. Perez visited a course I took this spring, called “Quests for Wisdom,” and said in a lecture, “Improvisation is a practicing of surrender. In this negotiation of the unknown, new knowledge is developed. Improvisation is a catalyst for change.” These poetry sites are a form of improvisation, a way to practice meeting the moment, in all its uncertainty, while practicing creative flexibility.

In this way, there is a commitment to new pathways of meaning-making. Perez also spoke of “fear training”— developing a musician’s ears to deal with fear while publicly demonstrating the creative process. Like jazz musicians on a stage, these poetic sites are places to practice being with fear— of the unknown, of connection, of vulnerability— while staying present.

The sites are also in conversation with conceptual artist Marina Abramović, especially her piece “The Artist Is Present,” where Abramović sat across from participants at a wooden table at the MoMA and silently offered her complete presence, her gaze. The only instructions were, “Sit silently with the artist for a duration of your choosing.” People waited in line for hours, for days, to be witnessed and to witness. Abramović wrote that, “I have to be transmitter and receiver in the same time… and be ready for the next visitor and the next one and the next one.” From her work, I’ve learned that the participants in line (or in the space where I am writing) are also essential to the site— they are witnesses of unknown territory.

I came into this program knowing that poetry mattered, that it had potential to create change, to offer brave spaces of connection. But I wasn’t expecting to discover the secret ways I believed, somewhere, that it mattered less than other forms of knowledge, the ways culture often diminished its (quieter and unscalable ways) of impact.

Reviewing the poems written here, I find myself remembering all of the moments filled with tears, with laughter, with silence. All the times my fingers left ink-covered prints, all the times I dragged my typewriter through heat and snow. In reviewing the following poems, I especially love the mistakes that I forgot to correct— it reminds me of the humility and messiness required of this work. This is just one way I know I’ve changed as a writer— I am more willing to take risks, with more capacity to trust the errors.

I honor the ongoingness of this vocation, with immense gratitude to all who hosted me in their spaces, to all who participated in these sites and offered me moments of their lives. It was, and is, a privilege to listen.

Love,

Raisa

I was honored to be at an All Staff meeting at HDS where you were bringing us poems. I treasure my poem "Calling in Hope". This is a beautiful essay. Thank you for sharing!

Just reading this — in awe 🤍