I spent my 30th birthday walking 30 miles through New York City with my beloveds and accidentally walked more than that… straight into my 40s.

There was mist and rain and sunlight. There were bowls of matzoh ball soup and stickers plastered on benches and long conversations filled with memories: the city of my twenties, filled with bad dates and good drinks and dramaic drafts of poems.

The route we walked was made for me by the ones I love, accompanied by ones I love (both virtually and IRL), and in that way, I felt led by love itself, and able to let go into the pain and joy of doing a hard thing in such a supported way. My partner organized the whole event. Folks offered snacks and funded meals and sent poems and quotes for the journey. A friend let us stay in her apartment. A friend so generously opened up her home so a group of us walkers could pee.

I even stopped into the restaurant where I used to work and felt time collapsing. I was suddenly 23, reporting for the brunch shift, not 30 and married, having lived a few of the things I so desperately hoped for. That restaurant looked exactly the same, light sparking through the large glass windows, wooden bar top still gleaming. My manager was still there, giving me the warmest hugs.

Other places, portals, had closed, and I found myself wondering: what street were they on? Were they ever there? What year was that? The many cities I lived in began to blur.

It was beautiful to walk part of this journey with my parents and my partner’s parents— to have parts of the walk be shaped by them, to ask about their stories and memories while holding so many questions about myself, about the world, right now.

I’ve been thinking about a quote by Rebecca Solnit for some time:

“Walking . . . is how the body measures itself against the earth.”

I measured my body against the earth this month— where I’ve been and where I’m going.

Writing, too, is another way of measuring, if not in numbers, than in sentences.

Earlier his month I read about the relationship beween walking, writing, and living in an essay by poet AR Ammons. In it, he says that poems resemble a walk in three ways:

“Each makes use of the whole body… as with a walk, a poem is not simply a mental activity: it has body, rhythm, feeling, sound, and mind, conscious and subconscious. The pace at which a poet walks (and thinks), his natural breath-length, the line he pursues, whether forthright and straight or weaving and meditative, his whole "air," whether of aimlessness or purpose - all these things and many more figure into the "physiology" of the poem he writes.”

“Every walk is unreproducible, as is every poem. Even if you walk exactly the same route each time - as with a sonnet - the events along the route cannot be imagined to be the same from day to day, as the poet's health, sight, his anticipations, moods, fears, thoughts cannot be the same. There are no two identical sonnets or villanelles. If there were, we would not know how to keep the extra one: it would have no separate existence. If a poem is each time new, then it is necessarily an act of discovery, a chance taken, a chance that may lead to fulfillment or disaster.

“…each turns, one or more times, and eventually returns—”

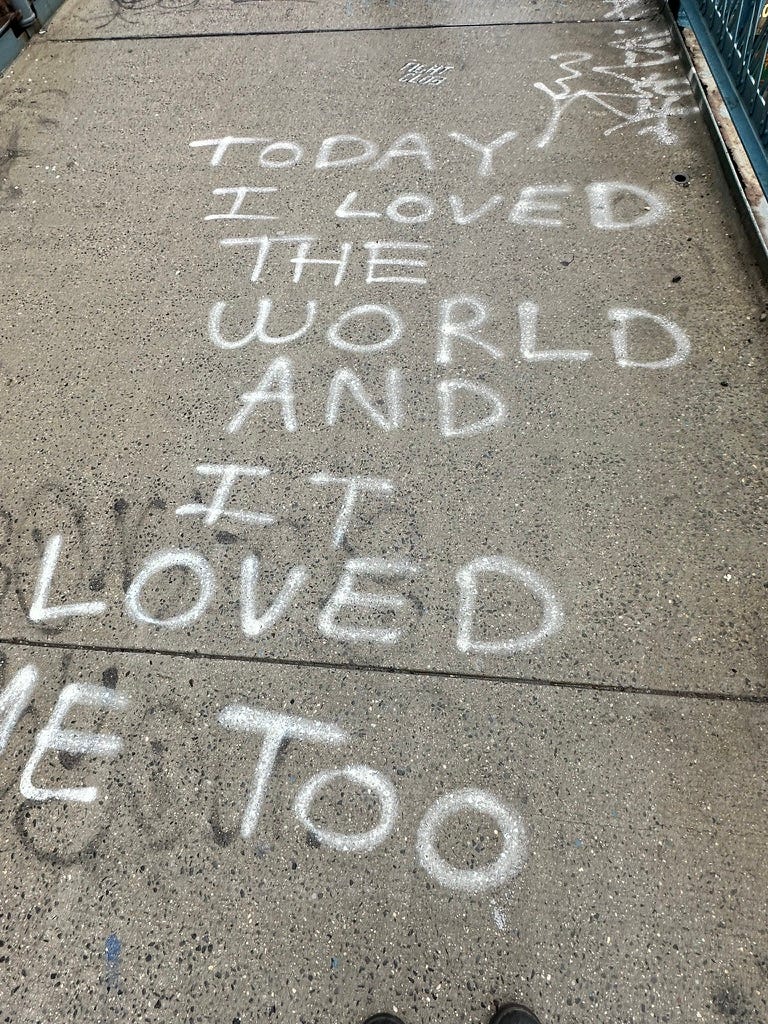

In this way, those walking days felt like writing the poem I want to live in— the poem that persists amidst so much collapse— against all odds, there is still the poem.

I am reminded of the joy in doing something difficult— a real crossing— and the support there for me.

We ended the walk at Walter de Maria’s Broken Kilometer. It felt like looking at the poemwalk— an attempted portrayal of something so wild, so mystical, so shining, it cannot be contained, and yet, somehow, laid out before us. A group of us sat on benches and stayed until the gallery closed.

“[De Maria] envisioned The Broken Kilometer within its own temporal cycle: the work ages over ten years and is then cleaned, resetting the aging process anew…”

And although I don’t get to be “reset”— I am heading forward into time, never getting my twenties back, and actually (usually) not wanting them back— I appreciate the awareness of how art, like a poem, like a decade, like a walk, like a body, has a temporal cycle— it ages.

Back to Ammon’s essay, there was no “point” to walking that far except that I am changed by it— in touch with something beautiful and mysterious, making way for surprises and experiences I could have never predicted.

There is no “usefulness” to a poem except that being with mystery is perhaps the most useful thing of all.

I’ll end with a last quote from R. Solnit:

“Walkers are ‘practitioners of the city,’ for the city is made to be walked. A city is a language, a repository of possibilities, and walking is the act of speaking that language, of selecting from those possibilities. Just as language limits what can be said, architecture limits where one can walk, but the walker invents other ways to go.”

Let us invent other ways to go.

With sore feet and a wild heart,

Raisa

It is always so interesting to me that, by the time we turn 30, we have already walked our 30th year~

The happiest of birthdays to you my dear Raisa… this 30 (+!) mile celebration could not have been more perfect.. your thoughtfulness overwhelms & inspires me!!! Much ❤️